"No, it's from Dharavi", he said. "I've seen it before."

When we got closer, I realised it was coming from the opposite side of the road, from the marshy land opposite the hutments. It seemed to come from a line of trucks parked on the road. There was none of the panic and shouting associated with a fire.

When we got closer, I realised it was coming from the opposite side of the road, from the marshy land opposite the hutments. It seemed to come from a line of trucks parked on the road. There was none of the panic and shouting associated with a fire.

We stopped for a closer look. Here's what we saw - in a clearing behind a low wall, a big rubbish heap was being burnt. Maybe they were burning the left-overs from the recycling factories - the thick smoke told me it was probably at least partly plastic. A young man was sitting there - he didn't move at all in the 10 minutes that I was there - I got the feeling he was watching over the fire. There were two bullock carts, transporting oil, the bullocks resting in preparation for the day ahead.

We stopped for a closer look. Here's what we saw - in a clearing behind a low wall, a big rubbish heap was being burnt. Maybe they were burning the left-overs from the recycling factories - the thick smoke told me it was probably at least partly plastic. A young man was sitting there - he didn't move at all in the 10 minutes that I was there - I got the feeling he was watching over the fire. There were two bullock carts, transporting oil, the bullocks resting in preparation for the day ahead.

I realised it was just another day in Dharavi. Nobody gave a damn about the dense smoke, although my chest burned from just 10 minutes exposure. Just across the road from the burning, the daily routine had begun. The water tanker had arrived and big plastic drums were being filled for the day.

I realised it was just another day in Dharavi. Nobody gave a damn about the dense smoke, although my chest burned from just 10 minutes exposure. Just across the road from the burning, the daily routine had begun. The water tanker had arrived and big plastic drums were being filled for the day.

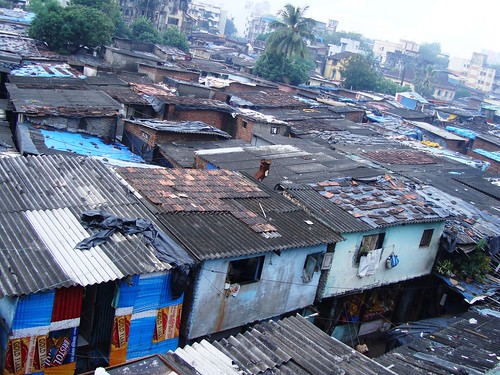

About 100 metres away, the shanties were already abuzz with activity. Little shops were open, and people were walking in the narrow lanes.

About 100 metres away, the shanties were already abuzz with activity. Little shops were open, and people were walking in the narrow lanes.

And naturally, since this was 7:00 a.m., every available inch of open space had been converted into a toilet. Little kids sat unmindful of passing traffic; while grown men found convenient bushes behind walls. The women, of course, had risen much earlier, while it was still dark, so they could have some desperately sought privacy.

My spirits sank at the sights I'd seen - pollution, dirt, stench...we're talking of Shanghai-like towers and skywalks and bridges, when we can't even get running water and toilets in place?

My spirits sank at the sights I'd seen - pollution, dirt, stench...we're talking of Shanghai-like towers and skywalks and bridges, when we can't even get running water and toilets in place?I was still thinking gloomy thoughts when we drove past a busy central thoroughfare and spotted several bright-eyed children going to school. Some of them were walking with siblings, others were riding pillion on their father's motorbikes. Many, especially the little ones, were walking with their mothers. I saw mothers carrying schoolbags and tiffin boxes and bright plastic water bottles, walking in that determined way that only mothers have, hustling their kids to school in time. After the depressing sights I had seen, the sight of these young kids was like a ray of sunshine. Here were children just like the ones I saw at my daughter's school; here were mothers with the same determination as me.

Still further down, I saw the Lijjat Papad van making its rounds, collecting papads and distributing fresh dough for making more. I thought of all the papad-makers I knew, women who supported their families through papad co-operatives. It lifted my spirits.

It's not all beyond repair, I told myself. There are good things too. Even among squalor and depressing conditions, Dharavi always manages to show a little bit of its bright side to anyone who cares to see it.

I remembered my first meeting with ragpickers from Dharavi a couple of years ago. They were sisters, giggling and collecting trash at Horniman Circle. I chatted with them only briefly; but talking to them changed me, transformed me from an outsider to an insider. As long as we don't turn our faces away from the reality of Dharavi, as long as we see commonality and shared humanity, there is hope yet - for the people of Dharavi, and for all of us in Mumbai who live side-by-side with it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment